Developmental dyslexia affects about 5% of the school population, across the ability range, mostly boys. Children with dyslexia have difficulty with reading and spelling.

Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed.

Across the dyslexic population, there is a spectrum of difficulty ranging from mild to severe.

Children with dyslexia often have co-occurring difficulties in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia.

The cause or causes of developmental dyslexia are not fully understood and are the major focus of current research. The picture, however, is likely to be complex. So far evidence suggests that:

- Dyslexia is sometimes an inherited condition – if one parent has dyslexia the child has between a 25-50% chance of also being dyslexic, and

- There are clear differences in the developing brain between people with and without dyslexia.

So far, there is no unique biological marker for dyslexia so educationalists rely on visible behavioural signs and symptoms, and these can be varied and have a variety of causes, not all of which can be attributed to dyslexia.

Understanding the specific brain functions that underlie dyslexia may allow researchers to develop more reliable diagnostic tests for younger children.

Research by Snowling (2000) found that dyslexic children often found it difficult to process and classify language sounds.

This impairment in phonology is thought to be due to a subtle abnormality in brain development, which can be directly linked to poor learning of written and spoken language.

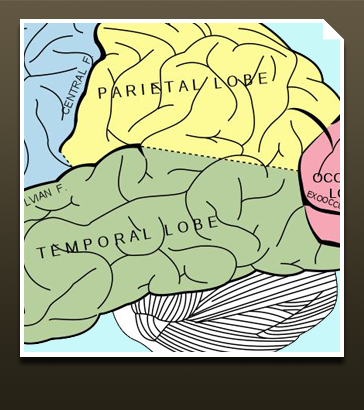

A number of brain imaging studies have found that, during reading, people with dyslexia have reduced activation in major parts of the reading and speech processing systems in the left hemisphere of the brain. Three parts of the reading system of the left hemisphere are activated during normal reading, whereas only two regions are activated in dyslexics. Dyslexics showed reduced activation in the 'temporal cortex', at the base of the left temporal lobe of the brain, which is associated with processing the form and sound of whole words. (Cao, 2006; Shaywitz, 2006)

There is some evidence from imaging studies of the brain of adults that effective teaching can bring about changes in the brain that improve performance.

It is useful to remember that good teaching and learning changes the brain and improves performance – even of children with neurological conditions.

Based on the available research evidence, the Rose Report on dyslexia (2009) advocated intervention programmes which have a strong, systematic phonic structure and are delivered sufficiently frequently to secure children's progress and consolidate learning. For children with dyslexia who respond very slowly to even the most effective of teaching, Rose recommends skilled, intensive, one-to –one interventions.

At the moment, the main type of support offered to children with dyslexia is intensive instruction in phonics. However, research at the Cambridge Centre for Neuroscience in Education suggests that interventions based on rhythm and even music may also be beneficial to children with dyslexia, at much earlier ages. Studies at the Centre have shown that:

- Being able to sing in time with music is predictive of syllable and rhyming skills, and

- Training in rhythm improves phonological awareness.

Several interventions based on musical and speech rhythms are now being developed at the Centre.

Consider a child with dyslexia in your class and build up a case study about this child taking account of the information in this package.

Consider:

- The nature of the child's dyslexia and how this manifests itself

- Associated difficulties

- The range of professionals that work with the child and what they do, and

- The range therapies and interventions used with the child.

Consider also:

- The child's strengths, and

- The barriers to learning and participation that the child faces.

What is done to remove barriers to learning and participation for that child – in your class and across the school? Identify personalised adjustments as well as more general adjustments that benefit the child you are focusing on and other children.

What could be improved in your own practice to remove barriers for the child? Identify one thing that you could change.

Change it and evaluate the impact on the child's participation and/or learning.

Snowling, M. (2000), Dyslexia, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford

Cao, F., Bitan, T., Chou, T. L., Burman, D. D. and Booth, J. R. (2006). "Deficient orthographic and phonological representations in children with dyslexia revealed by brain activation patterns". Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 47 (10): 1041-50.

Shaywitz, B. A., Lyon, GR. and Shaywitz, S. E. (2006). "The role of functional magnetic resonance imaging in understanding reading and dyslexia". Developmental neuropsychology. 30 (1): 613-32.

Cambridge Centre for Neuroscience in Education

Shaywitz ,S. (2003) Overcoming Dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for overcoming reading problems at any level, New York: Knopf