Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention deficit disorder (ADD) is characterised by inappropriate impulsiveness, chronic inattentiveness and, sometimes, hyperactivity.

Children with ADHD/ADD may find it difficult to establish relationships with adults and other children because they tend to behave in a way that both adults and children find difficult. For this reason, children with ADHD sometimes develop secondary emotional difficulties.

Boys are diagnosed with ADHD five times more frequently than girls.

Research suggests that ADHD may have a genetic basis leading to a subtle brain dysfunction which causes deficiency in neurotransmission in the brain cells.

Genetic research also suggests that ADHD may be the result of abnormalities to the dopamine system, which is concerned with the regulation of movement.

ADHD is usually diagnosed when:

- Several symptoms associated with impulsiveness and chronic inattentiveness have been present for several months

- These symptoms are inconsistent with the child's developmental level, and

- The symptoms are presenting significant barriers to learning a school and being part of family life at home.

But many young children fit this profile at some time in their childhood because the ability to sustain attention and keep still for long periods develops gradually over time.

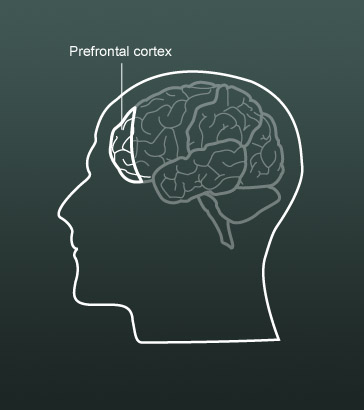

For a child to be able to sustain attention, the prefrontal cortex, which is concerned with self-control, must have reached a certain level of maturity. However, the frontal lobes of the brain continue to develop into adolescence or early adulthood and develop more slowly in some children than others. This can lead to over-diagnosis when an immaturity of the brain is mistaken for ADHD.

At present there are no biological markers for ADHD but, in future, more refined methods of behavioural testing, informed by findings from neuroscience has the potential to improve diagnosis for ADHD.

Early brain scanning evidence (Castellanos et al) demonstrated that two regions of the brain were smaller in boys with ADHD than in those without ADHD:

- The prefrontal cortex, which plays an important part in planning, making decisions, attention control and the inhibition of inappropriate behaviour, and

- Regions of the basal ganglia, which are involved in generating movements.

These two areas communicate with each other. Whether the basal ganglia generate movement or not depends on signals sent from the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex can determine when and how someone should act, but crucially in the case of ADHD, when a movement should not occur.

Inhibition is a crucial function of the frontal lobes, and as mentioned earlier, this develops gradually throughout childhood and into adolescence.

The brain's inhibitory function helps us to act appropriately in different social contexts. Young children, whose frontal cortex is not fully developed, find it much more difficult to do this but, in typically developing children, their ability to do this improves as they get older. Children with ADHD continue to find it difficult to inhibit behaviour and sustain attention.

This suggests that frontal lobe inhibitory control is not working effectively in children with ADHD, perhaps because the frontal lobes develop at a much slower rate.

Many children with ADHD are given prescription medication to treat their condition. The medication most commonly prescribed is methylphenidate (Ritalin).

Methylphenidate works by affecting some of the natural chemicals that are found in the brain. In particular, it increases the activity of chemicals called dopamine and noradrenaline in areas of the brain that play a part in controlling attention and behaviour. These areas seem to be underactive in children with ADHD. It is thought increasing the activity of these chemicals improves the function of these underactive parts of the brain.

Medication cannot cure ADHD but it can help them behave in a more acceptable manner.

For many children with ADHD medication helps them:

- Become less aggressive

- Interact more effectively with others

- Remain more focused, and

- Become less impulsive and interactive.

The prescription of medication for ADHD is controversial. There can be side-effects, including headaches, irritability and slow growth and some children do not like the way they feel when they are taking medication. If medication is seen as the whole answer then other needs within the child's life can be overlooked.

Where medication is used evidence suggests that it is most effective as part of a multi-modal approach, eg in conjunction with:

- Therapy

- Educational intervention to address any learning difficulties that the child may have, and

- The use of particular behavioural strategies at home and at school.

Because of concerns around reliance on medication to manage ADHD and because self-control has been found to be an important predictor of academic success, research is underway to investigate whether cognitive training programmes can influence brain development, so that self-control can be developed through appropriate teaching.

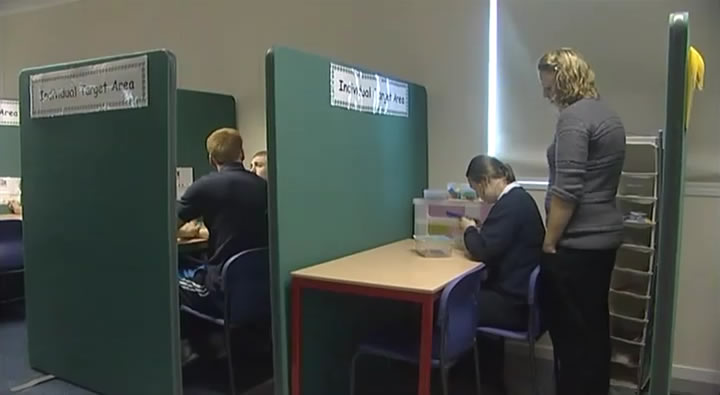

A range of teaching approaches that may be successful with children with ADHD were set out at level B of this module.

They included:

- Providing structure and predictability

- Reducing distractions

- Adapting tasks, and

- Staying positive.

Listen to Gavin, the head of an intensive support centre in a special school, describing his approach to children's behavioural difficulties. Notice how staff try to help children to develop self-control.

Before the frontal cortex is fully mature, adults play an important role in inhibiting unacceptable behaviour and promoting positive behaviour in children. Where these external controls seem not to be working or a child seems unable to make use of them in a sustained way over a period of time, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can be diagnosed.

ODD is only a persistent problem for a minority of children and very few go on to develop serious antisocial behaviour. Although there has not been much research on the neurological causes of ODD, the pattern of its development and its association with ADHD point to aspects of brain development as a likely cause.

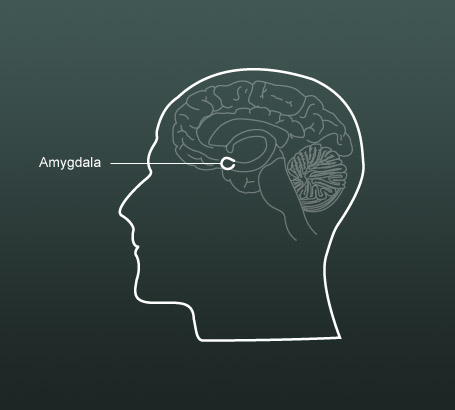

Psychopathy in adults sometimes starts with conduct disorders in children. There is some evidence (Blair, 2005) that there may be a rare neurodevelopmental disorder that leads to pychopathy in adults and that this may have a genetic component. Blair suggests that psychopathy may be caused by poor functioning of the amygdala, which controls emotion and normally responds to expressions of sadness and fear in other people.

Lead some staff development to introduce colleagues to the research on the neurological basis of ADHD. You may wish to read around the subject a little more widely to inform your planning.

The purpose of this staff development is to raise questions, identify issues and start a dialogue as the first step to auditing and developing practice across the school. If you can, involve other professionals who work with children with ADHD to participate and contribute to the discussion.

Make a list of the questions/issues raised by the discussions.

Cooper, P. and Bilton, K. (1996) Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. London: David Fulton.

Hughes, L. and Cooper, P. (2007) Understanding and Supporting Children with ADHD: Strategies for parents and other professionals. London: Sage Publications.

Thompson, R. (1993) The Brain: A Neuroscience primer (2nd edn). New York: Freeman.

Blair, J. (2005) The Psychopath: Emotion and the Brain, Oxford, Blackwell.

Touchette, P. and Howard, J. (1984) Errorless learning: reinforcement contingencies and stimulus control transfer in delayed prompting, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 17 (2), 175–188. US Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services.

Special Education Programs (2004) Teaching Children with Attention Deficit Disorder: Instructional strategies and practices. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.