Autism is a lifelong developmental disability. It is estimated six people in every thousand have some form of autism, with more males being affected than females.

Autism is characterised by:

- Difficulties in communication and social interaction, and

- Restricted interests and inflexible behaviour.

Autism is a spectrum condition, which means that, while all people with autism share certain difficulties, their condition will affect them in different ways and to different extents. For this reason people with autism are sometimes said to have an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or an Autism Spectrum Condition (ASD).

The three main areas of difficulty which all people with autism share are sometimes known as the 'triad of impairments'. They are difficulty with social:

- Communication

- Interaction, and

- Imagination.

As well as the triad of impairments, people with autism may have:

- A love of routines

- Sensory sensitivity

- Special interests, and

- Learning disabilities.

Some children on the autism spectrum are affected very mildly and their early development is not noticeably abnormal. These children are said to have Asperger syndrome. Diagnosis is, therefore, often made quite late.

Children with Asperger syndrome often have average, or above average, intelligence and their desire to learn social rules can camouflage the extent of their communication difficulties.

The causes of autism are still being investigated, however, research suggests that the cause is likely to be a genetic predisposition that affects brain development before birth.

Autism is not, as was once thought, caused by upbringing or social circumstances.

Early research into autism involved techniques from experimental cognitive psychology which led to the description of a number of 'cognitive defects' associated with autism. One of the proposed deficits is with theory of mind.

One theory that has been postulated to explain some of the observed characteristics of autism is that people with autism lack a 'theory of mind'.

Theory of mind describes the ability to attribute desires, feelings and thoughts to others to explain their behaviour. Other terms used to describe this are 'mentalizing' and 'empathising'.

Most people without autism can mentalize easily. This might be because there is an area of the brain that is responsible for mentalizing. Some scientists (Baron-Cohen, Leslie & Frith 1985) have suggested that, in autism, this area of the brain is faulty.

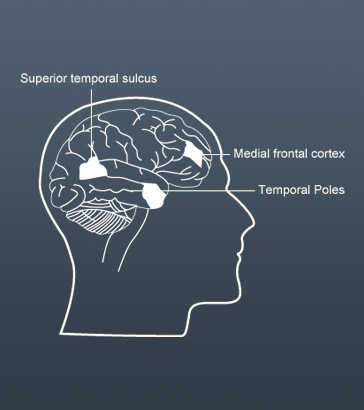

Brain imaging has revealed those parts of the brain that are active when adults without autism engage in automatic mentalizing.

They are:

- The medial prefrontal cortex – involved in monitoring the internal states of self and others

- The superior temporal sulcus – important for analysing people's movements and actions, and

- The temporal poles – involved in processing emotions.

Brain scans of very able people with Asperger syndrome performing mentalizing tasks show that the three brain regions involved in mentalizing are less active.

There is some evidence, from anatomical studies, of abnormally developing connections in the brains of children with autism.

Other studies (Courchesne et al, 2011) have found that the brains of many people with autism are bigger and heavier than the brains of non-autistic people, despite being the same size at birth.

In normal brain development connections between brain cells at first multiply and then are 'pruned' away according to how much they are used. It is possible that appropriate pruning does not occur in autism.

Just because autistic children lack the innate basis for 'theory of mind' doesn't mean they can't learn about mentalizing through explicit teaching.

However, they often are not able to generalisation their learning from one situation to another, so different situations and contexts will need to be taught separately, and the implications of actions, facial expressions, gestures and words, that may seem obvious to most people, will need to be spelt out.

Information from neuroscience can inform practice in schools. Watch this video in which Sarah, a teacher, uses a social story with Fiona. The social story helps Fiona to understand the implications of her actions as well as helping her to understand how to behave appropriately with other children at playtime.

Notice how Fiona refers to this information every playtime to remind herself how to behave. Sarah talks about pupils having a range of social stories that they can refer to when they need to, to help them to remember the protocol in different social situations.

Lead some staff development to introduce colleagues to the research on the neurological basis of autism. You may wish to read around the subject a little more widely to inform your planning.

The purpose of this staff development is to raise questions, identify issues and start a dialogue, as the first step to auditing and developing practice across the school (Level D). If you can, involve other professionals who work with children with autism to participate and contribute to the discussion.

Make a list of the questions/issues raised by the discussions.

Brooks, T. (2010) Developing a Learning Environment which Supports Children with Profound Autistic Spectrum Disorder to Engage as Effective Learners (PhD thesis). Worcester: University of Worcester.

Frith, Uta (2003) Autism: Explaining the Enigma, 2nd Edition, Oxford, Blackwell.

Happe, F. (2007), Autism: an introduction to psychological theory.

Mesibov, G., Shea, V. and Schopler, E. (2005) The TEACCH Approach to Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York: Springer Inc.

Sainsbury, C. (2000) Martian in the Playground: Understanding the Schoolchild with Asperger's Syndrome, Bristol UK: Lucky Duck Publishing.

Tutt, R., Powell, S. and Thornton, M. (2006) Educational approaches in autism: what we know about what we do, Educational Psychology in Practice, 22 (1), 69–81.

Wing, L. and Gould, J. (1979) Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: epidemiology and classification, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9, 11–29.