Research indicates that we need to intervene early to make sure that our children get the best possible

start in life.

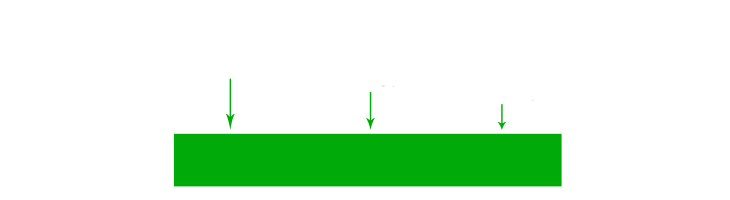

...babies are born with 25 per cent of their brains developed, and there is then a rapid period of development so that by

the age of 3 their brains are 80 per cent developed.

In that period, neglect, the wrong type of parenting and other adverse experiences can have a profound effect on how children

are emotionally 'wired'. This will deeply influence their future responses to events and their ability to empathise with other

people.

Allen, 2011

A plausible case can be made for the viability and potential effectiveness of primary and secondary prevention

of learning disabilities... The vast majority of the options for prevention involve altering the social and environmental

context in which children in the UK grow up. Some of these interventions are relevant to all children (eg reducing exposure

to child poverty and economic inequality). Some are more specific to children with learning disabilities and the families

who support them (eg early intervention for children with developmental delay, short breaks).

Emerson, 2011

...disability remains one of the most significant indicators of greater chances of living in poverty.

Field, 2010

...recent research in England has documented social gradients across the full range of severity of learning

disability...

When controlling for the effects of local authority, neighbourhood deprivation and pertinent child characteristics (age, gender,

ethnicity), children aged 7-15 in England growing up in households that are eligible for free school meals are...80% more

likely to be identified as having a Special Educational Need (at School Action Plus or above) associated with Profound Multiple

Learning Difficulty (PMLD).

Emerson, 2011

Family Support services proved the most useful aspect of Sure Start for families with children with more

complex needs. These services help families to cope in crises, obtain services and benefits, gain skills and confidence in

supporting their child's development and get some respite from their caring responsibilities. Home-visiting was particularly

important in reaching isolated and vulnerable families...

The availability of specialist health services like speech and language therapy and mental health outreach was significant

for these young children, enabling preventive work to occur, and developing parents' skills in promoting their child's development

and managing their behaviour.

Pinney, 2007

Initial findings from...indicative studies suggest that early years interventions for disabled children can lead to:

- Enhanced social and communication skills;

- Greater inclusion and participation in mainstream settings;

- Increased integration with the wider family;

- Improved behaviour;

- Enhanced cognitive development.

Improvements in outcomes for the families of disabled children may also include:

- Positive perceptions and attitudes concerning their child's disability and their parental situation;

- Improved emotional wellbeing (including lower levels of parental stress, emotional distress, anxiety and depression), and lower incidence of maternal mental health issues;

- Better access to services.

In summary, the role that societies can play in early child development is to support initiatives that bring young children into contact with environments that have the following six characteristics:

- Exploration is encouraged;

- Mentoring in basic skills is provided;

- The child's developmental advances are celebrated;

- Development of new skills is guided and extended;

- There is protection from inappropriate disapproval, teasing, or punishment;

- The language environment is rich and responsive.

Research the different early intervention approaches available to families of children with SLD/PMLD/CLDD and their effectiveness; for example:

- EarlyBird (National Autistic Society);

- Family Nurse Partnerships;

- Incredible Years Programmes;

- Portage;

- Sure Start Children's Centres;

- Team Around the Child.

What characteristics of these approaches might be applicable within your setting?

Allen, G. (2011) Early Intervention: The next steps. London: Cabinet Office (accessed: 12.1.12).

Carpenter, B. (2010) Disadvantaged, deprived and disabled, Special Children, 193, 42-45.

Emerson, E., Hatton, C. and Robertson, J. (2011) Prevention and Social Care for Adults with Learning Disabilities. London: London School of Economics and Political Science (accessed 12.1.12).

Field, F. (2010) The Foundation Years: Preventing poor children becoming poor adults. London: HM Government (accessed 12.1.12).

Maggi, S., Irwin, L.G., Siddiqi, A., Poureslami, I., Hertzman, E. and Hertzman, C. (2005) International Perspectives on Early Child Development. Geneva: World Health Organisation (online 12.1.12).

Martin, K., Wilkin, A., Morris, M., O'Donnell, L., and Sharp, C. (2009) Improving the Wellbeing of Disabled Children through Early Years Interventions (Age 0–8). London: Centre for Excellence and Outcomes in Children and Young People's Services (C4EO) (accessed 12.1.12).

Pinney, A. (2007) A Better Start: Children and families with special needs and disabilities in Sure Start Local Programmes. Annesley: DfES Publications (accessed 12.1.12).

If you want to read around the subject take a look at these four titles.

Allen, G. (2011) Early Intervention: Smart Investment, Massive Savings. London: HM Government (accessed: 12.1.12).

Munro, E. (2011) The Munro Review of Child Protection: A child-centred system. London: Department for Education (accessed 12.1.12).

Odom, S.L. and Wolery, M. (2003) A unified theory of practice in early intervention/early childhood special education: evidence-based practices, Journal of Special Education, 37, 164-173.

Tickell, C. (2011) The Early

Years: Foundations for life, health and learning. London: HM

Government (accessed 12.1.12).